Step2ward

Who among us doesn’t have a similar story about a song that touched us? Whether attending a concert, listening to the radio, or singing in the shower, there’s something about music that can fill us with emotion, from joy to sadness.

Music impacts us in ways that other sounds don’t, and for years now, scientists have been wondering why. Now they are finally beginning to find some answers. Using fMRI technology, they’re discovering why music can inspire such strong feelings and bind us so tightly to other people.

“Music affects deep emotional centers in the brain, “ says Valorie Salimpoor, a neuroscientist at McGill University who studies the brain on music. “A single sound tone is not really pleasurable in itself; but if these sounds are organized over time in some sort of arrangement, it’s amazingly powerful.”

“That’s a big deal, because dopamine is released with biological rewards, like eating and sex, for example,” says Salimpoor. “It’s also released with drugs that are very powerful and addictive, like cocaine or amphetamines.”

There’s another part of the brain that seeps dopamine, specifically just before those peak emotional moments in a song: the caudate nucleus, which is involved in the anticipation of pleasure. Presumably, the anticipatory pleasure comes from familiarity with the song—you have a memory of the song you enjoyed in the past embedded in your brain, and you anticipate the high points that are coming. This pairing of anticipation and pleasure is a potent combination, one that suggests we are biologically-driven to listen to music we like.

But what happens in our brains when we like something we haven’t heard before? To find out, Salimpoor again hooked up people to fMRI machines. But this time she had participants listen to unfamiliar songs, and she gave them some money, instructing them to spend it on any music they liked.

When analyzing the brain scans of the participants, she found

that when they enjoyed a new song enough to buy it, dopamine was again

released in the nucleus accumbens. But, she also found increased

interaction between the nucleus accumbens and higher, cortical

structures of the brain involved in pattern recognition, musical memory,

and emotional processing.

This finding suggested to her that when people listen to unfamiliar music, their brains process the sounds through memory circuits, searching for recognizable patterns to help them make predictions about where the song is heading. If music is too foreign-sounding, it will be hard to anticipate the song’s structure, and people won’t like it—meaning, no dopamine hit. But, if the music has some recognizable features—maybe a familiar beat or melodic structure—people will more likely be able to anticipate the song’s emotional peaks and enjoy it more. The dopamine hit comes from having their predictions confirmed—or violated slightly, in intriguing ways.

“It’s kind of like a roller coaster ride,” she says, “where you know what’s going to happen, but you can still be pleasantly surprised and enjoy it.”

Salimpoor believes this combination of anticipation and intense emotional release may explain why people love music so much, yet have such diverse tastes in music—one’s taste in music is dependent on the variety of musical sounds and patterns heard and stored in the brain over the course of a lifetime. It’s why pop songs are, well, popular—their melodic structures and rhythms are fairly predictable, even when the song is unfamiliar—and why jazz, with its complicated melodies and rhythms, is more an acquired taste. On the other hand, people tend to tire of pop music more readily than they do of jazz, for the same reason—it can become too predictable.

Her findings also explain why people can hear the same song over and over again and still enjoy it. The emotional hit off of a familiar piece of music can be so intense, in fact, that it’s easily re-stimulated even years later.

“If I asked you to tell me a memory from high school, you would be able to tell me a memory,” says Salimpoor. “But, if you listened to a piece of music from high school, you would actually feel the emotions.”

In one study, Large and colleagues had participants listen to one of two variations on a Chopin piece: In version one, the piece was played as it normally is, with dynamic variations, while in version two, the piece was played mechanically, without these variations. When the participants listened to the two versions while hooked up to an fMRI machine, their pleasure centers lit up during dynamic moments in the version one song, but didn’t light up in version two. It was as if the song had lost its emotional resonance when it lost its dynamics, even though the “melody” was the same.

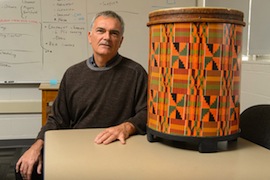

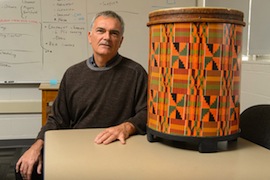

Ed Large, University of Connecticut Peter Morenus/UConn Photo

“In

fact, when we debriefed the listeners after the experiment was over,

they didn’t even recognize that we were playing the same piece of

music,” says Large.

Ed Large, University of Connecticut Peter Morenus/UConn Photo

“In

fact, when we debriefed the listeners after the experiment was over,

they didn’t even recognize that we were playing the same piece of

music,” says Large.

When playing the more dynamic version, Large also observed activity in the listener’s mirror neurons —the neurons implicated in our ability to experience internally what we observe externally. The neurons fired more slowly with slower tempos, and faster with faster tempos, suggesting that mirror neurons may play an important role in processing musical dynamics and affecting how we experience music.

“Musical rhythms can directly affect your brain rhythms, and brain rhythms are responsible for how you feel at any given moment,” says Large.

That’s why when people get together and hear the same music—such as in a concert hall—it tends to make their brains synch up in rhythmic ways, inducing a shared emotional experience, he says. Music works in much the same way language works—using a combination of sound and dynamic variations to impart a certain understanding in the listener.

“If I’m a performer and you’re a listener, and what I’m playing really moves you, I’ve basically synchronized your brain rhythm with mine,” says Large. “That’s how I communicate with you.”

But if our brains all synch up when we hear the same basic dynamic differences in music, why don’t we all respond with the same pleasure?

Large, like Salimpoor, says that this difference in preference is due to how our neurons are wired together, which in turn is based on our own, personal history of listening to or performing music. Rhythm is all about predictability, he says, and our predictions about music start forming from a pretty early age onward. He points to the work of Erin Hannon at the University of Nevada who found that babies as young as 8 months old already tune into the rhythms of the music from their own cultural environment.

So while activity in the nucleus accumbens may signal emotional pleasure, it doesn’t explain it, says Large. Learning does. That’s why musicians—who’ve usually been exposed to more complicated musical patterns over time—tend to have more varied musical tastes and enjoy more avant-garde musical traditions than non-musicians. Social contexts are also important, he adds, and can affect your emotional responses.

“Liking is so subjective,” he says. “Music may not sound any different to you than to someone else, but you learn to associate it with something you like and you’ll experience a pleasure response.”

Perhaps that explains why I love “Solsbury Hill” so much. Not only does its unusual rhythm intrigue me—as a musician, I still have the urge to count it out from time to time—but it reminds me of where I was when I first heard the song: sitting next to a cute guy I had a crush on in college. No doubt my anticipatory pleasure centers were firing away for a multitude of reasons.

And, luckily, now that the pleasure pathways are now deeply embedded in my brain, the song can keep on giving that sweet emotional release.

Why We Love Music

I still remember when I first heard the song by Peter Gabriel, “Solsbury Hill.” Something about that song—the lyrics, the melody, the unusual 7/4 time signature—gave me chills. Even now, years later, it still can make me cry.Who among us doesn’t have a similar story about a song that touched us? Whether attending a concert, listening to the radio, or singing in the shower, there’s something about music that can fill us with emotion, from joy to sadness.

Music impacts us in ways that other sounds don’t, and for years now, scientists have been wondering why. Now they are finally beginning to find some answers. Using fMRI technology, they’re discovering why music can inspire such strong feelings and bind us so tightly to other people.

“Music affects deep emotional centers in the brain, “ says Valorie Salimpoor, a neuroscientist at McGill University who studies the brain on music. “A single sound tone is not really pleasurable in itself; but if these sounds are organized over time in some sort of arrangement, it’s amazingly powerful.”

How music makes the brain happy

How powerful? In one of her studies, she and her colleagues hooked up participants to an fMRI machine and recorded their brain activity as they listened to a favorite piece of music. During peak emotional moments in the songs identified by the listeners, dopamine was released in the nucleus accumbens, a structure deep within the older part of our human brain.“That’s a big deal, because dopamine is released with biological rewards, like eating and sex, for example,” says Salimpoor. “It’s also released with drugs that are very powerful and addictive, like cocaine or amphetamines.”

There’s another part of the brain that seeps dopamine, specifically just before those peak emotional moments in a song: the caudate nucleus, which is involved in the anticipation of pleasure. Presumably, the anticipatory pleasure comes from familiarity with the song—you have a memory of the song you enjoyed in the past embedded in your brain, and you anticipate the high points that are coming. This pairing of anticipation and pleasure is a potent combination, one that suggests we are biologically-driven to listen to music we like.

But what happens in our brains when we like something we haven’t heard before? To find out, Salimpoor again hooked up people to fMRI machines. But this time she had participants listen to unfamiliar songs, and she gave them some money, instructing them to spend it on any music they liked.

Valorie Salimpoor, McGill University

This finding suggested to her that when people listen to unfamiliar music, their brains process the sounds through memory circuits, searching for recognizable patterns to help them make predictions about where the song is heading. If music is too foreign-sounding, it will be hard to anticipate the song’s structure, and people won’t like it—meaning, no dopamine hit. But, if the music has some recognizable features—maybe a familiar beat or melodic structure—people will more likely be able to anticipate the song’s emotional peaks and enjoy it more. The dopamine hit comes from having their predictions confirmed—or violated slightly, in intriguing ways.

“It’s kind of like a roller coaster ride,” she says, “where you know what’s going to happen, but you can still be pleasantly surprised and enjoy it.”

Salimpoor believes this combination of anticipation and intense emotional release may explain why people love music so much, yet have such diverse tastes in music—one’s taste in music is dependent on the variety of musical sounds and patterns heard and stored in the brain over the course of a lifetime. It’s why pop songs are, well, popular—their melodic structures and rhythms are fairly predictable, even when the song is unfamiliar—and why jazz, with its complicated melodies and rhythms, is more an acquired taste. On the other hand, people tend to tire of pop music more readily than they do of jazz, for the same reason—it can become too predictable.

Her findings also explain why people can hear the same song over and over again and still enjoy it. The emotional hit off of a familiar piece of music can be so intense, in fact, that it’s easily re-stimulated even years later.

“If I asked you to tell me a memory from high school, you would be able to tell me a memory,” says Salimpoor. “But, if you listened to a piece of music from high school, you would actually feel the emotions.”

How music synchronizes brains

Ed Large, a music psychologist at the University of Connecticut, agrees that music releases powerful emotions. His studies look at how variations in the dynamics of music—slowing down or speeding up of rhythm, or softer and louder sounds within a piece, for example—resonate in the brain, affecting one’s enjoyment and emotional response.In one study, Large and colleagues had participants listen to one of two variations on a Chopin piece: In version one, the piece was played as it normally is, with dynamic variations, while in version two, the piece was played mechanically, without these variations. When the participants listened to the two versions while hooked up to an fMRI machine, their pleasure centers lit up during dynamic moments in the version one song, but didn’t light up in version two. It was as if the song had lost its emotional resonance when it lost its dynamics, even though the “melody” was the same.

Ed Large, University of Connecticut Peter Morenus/UConn Photo

Ed Large, University of Connecticut Peter Morenus/UConn Photo When playing the more dynamic version, Large also observed activity in the listener’s mirror neurons —the neurons implicated in our ability to experience internally what we observe externally. The neurons fired more slowly with slower tempos, and faster with faster tempos, suggesting that mirror neurons may play an important role in processing musical dynamics and affecting how we experience music.

“Musical rhythms can directly affect your brain rhythms, and brain rhythms are responsible for how you feel at any given moment,” says Large.

That’s why when people get together and hear the same music—such as in a concert hall—it tends to make their brains synch up in rhythmic ways, inducing a shared emotional experience, he says. Music works in much the same way language works—using a combination of sound and dynamic variations to impart a certain understanding in the listener.

“If I’m a performer and you’re a listener, and what I’m playing really moves you, I’ve basically synchronized your brain rhythm with mine,” says Large. “That’s how I communicate with you.”

Different notes for different folks

Other research on music supports Large’s theories. In one study, neuroscientists introduced different styles of songs to people and monitored brain activity. They found that music impacts many centers of the brain simultaneously; but, somewhat surprisingly, each style of music made its own pattern, with uptempo songs creating one kind of pattern, slower songs creating another, lyrical songs creating another, and so on. Even if people didn’t like the songs or didn’t have a lot of musical expertise, their brains still looked surprisingly similar to the brains of people who did.But if our brains all synch up when we hear the same basic dynamic differences in music, why don’t we all respond with the same pleasure?

Large, like Salimpoor, says that this difference in preference is due to how our neurons are wired together, which in turn is based on our own, personal history of listening to or performing music. Rhythm is all about predictability, he says, and our predictions about music start forming from a pretty early age onward. He points to the work of Erin Hannon at the University of Nevada who found that babies as young as 8 months old already tune into the rhythms of the music from their own cultural environment.

So while activity in the nucleus accumbens may signal emotional pleasure, it doesn’t explain it, says Large. Learning does. That’s why musicians—who’ve usually been exposed to more complicated musical patterns over time—tend to have more varied musical tastes and enjoy more avant-garde musical traditions than non-musicians. Social contexts are also important, he adds, and can affect your emotional responses.

“Liking is so subjective,” he says. “Music may not sound any different to you than to someone else, but you learn to associate it with something you like and you’ll experience a pleasure response.”

Perhaps that explains why I love “Solsbury Hill” so much. Not only does its unusual rhythm intrigue me—as a musician, I still have the urge to count it out from time to time—but it reminds me of where I was when I first heard the song: sitting next to a cute guy I had a crush on in college. No doubt my anticipatory pleasure centers were firing away for a multitude of reasons.

And, luckily, now that the pleasure pathways are now deeply embedded in my brain, the song can keep on giving that sweet emotional release.

0 comments:

Post a Comment